Key words: Complex traits, Evolutionary genetics, Transcriptomics, Genomics, venom evolution.

Current Research:

I am currently working with teleost fish systems, taking full advantage of their remarkable diversity and well-documented genetic resources to explore the functional genomics of various tissue systems. My objective is to identify genes and biological processes that have never before been associated with the functioning of distinct tissue systems. The discovery of these candidate genes could resolve the intricate functionality of various tissues and pave the way for them to become potential targets for gene therapy.

Previous Research:

Understanding the molecular and genetic mechanisms that contribute to trait evolution is at the heart of evolutionary biology. However, the complex nature of most traits makes this difficult to answer. Here, the snake venom system offers particular advantages. Venom is composed of a proteinaceous cocktail, where each venom component can be traced to an individual gene, thereby providing an unprecedented level of genetic tractability. Using this solid genotype-phenotype relationship, I uncover ways evolution shapes and gives rise to complex traits.

Repeated evolution using the same building blocks

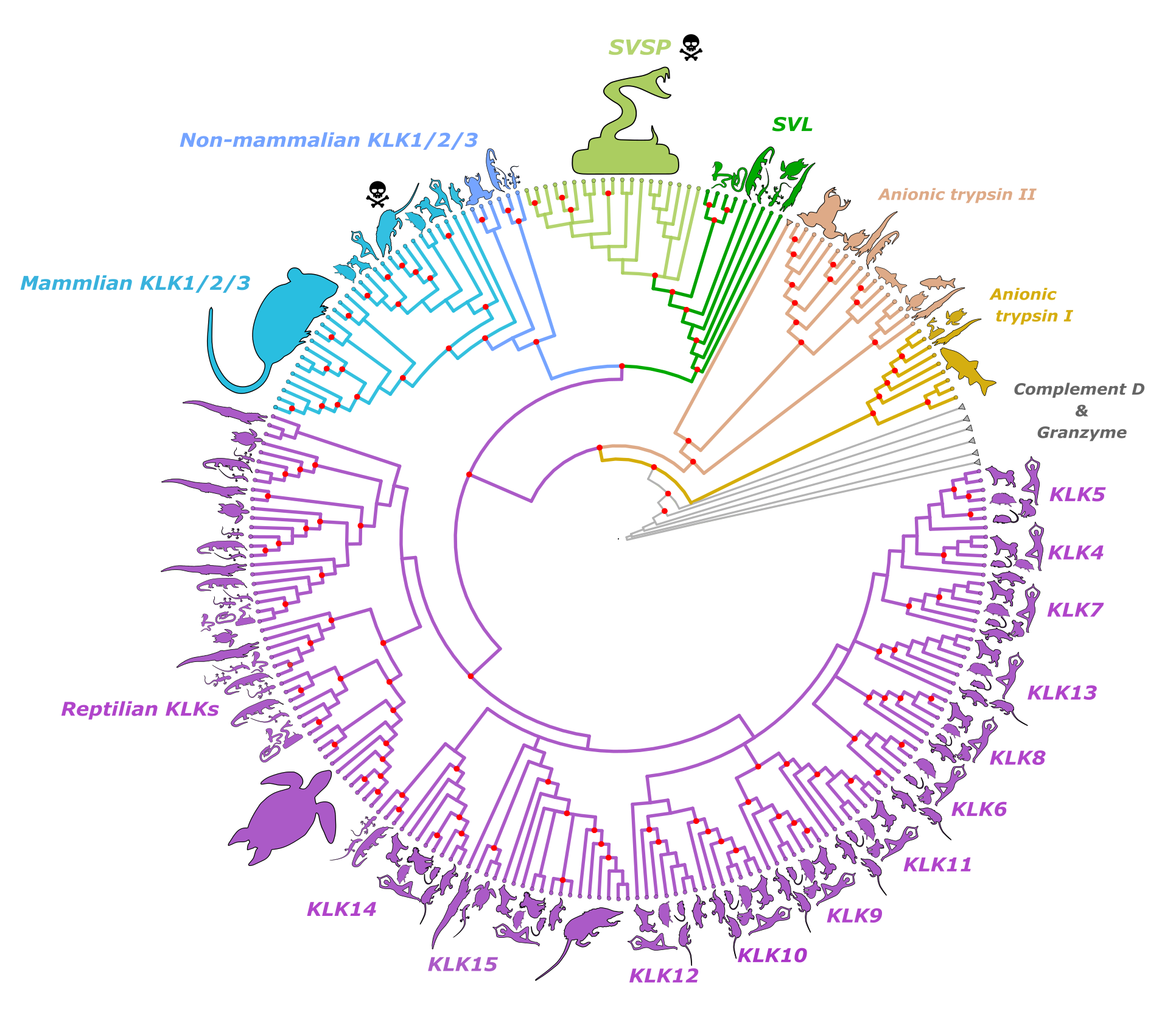

Evolution can occur with surprising predictability when faced with similar ecological challenges. How and why this repeatability occurs remains a central question in evolutionary biology, but the complexity of most traits makes it challenging to answer. Venoms of mammals and reptiles are believed to have independently evolved serine protease (SP) based toxins. But so far, the genetic path to this recruitment hasn’t been explored. Using comparative genomics and phylogenetics, we showed that SP-based toxins are homologous and originated from the same ancestral gene. Our results illustrate how a conserved genetic framework can still be a source of phenotypic novelty.

Evolution can occur with surprising predictability when faced with similar ecological challenges. How and why this repeatability occurs remains a central question in evolutionary biology, but the complexity of most traits makes it challenging to answer. Venoms of mammals and reptiles are believed to have independently evolved serine protease (SP) based toxins. But so far, the genetic path to this recruitment hasn’t been explored. Using comparative genomics and phylogenetics, we showed that SP-based toxins are homologous and originated from the same ancestral gene. Our results illustrate how a conserved genetic framework can still be a source of phenotypic novelty.

A robust system for homeostasis can enable further molecular diversification

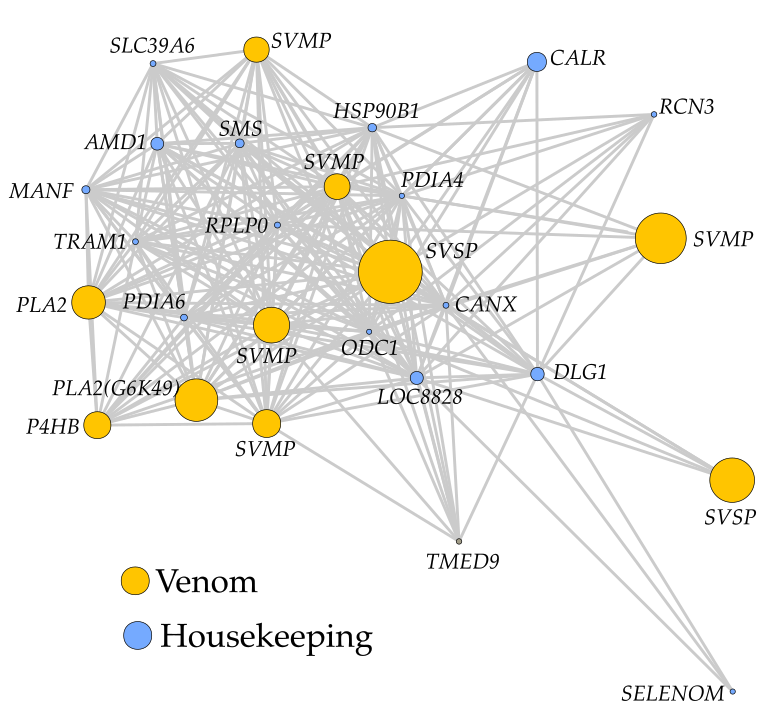

No biological process acts in isolation. Instead, even highly specific systems are regulated by feedback loops and interactions with other processes. Unfortunately, this perspective often takes a back seat because biological traits are complex, and it is impossible to account for all interactions. However, a network-based approach can provide some leeway. By constructing a co-expression network of a viper venom gland, we identified the numerous processes working together to produce venom. We identified genes involved in protein folding and degradation to be strongly co-expressed with venom genes. This ‘metavenom’ was key to the evolution of snake venom. It provided tenacity to the venom system to withstand high protein loads and enable the recruitment of diverse proteins into the venom cocktail. This study provides many fundamental contributions to our understanding of the kind of changes, or rather conserved changes needed to enable trait diversification.

No biological process acts in isolation. Instead, even highly specific systems are regulated by feedback loops and interactions with other processes. Unfortunately, this perspective often takes a back seat because biological traits are complex, and it is impossible to account for all interactions. However, a network-based approach can provide some leeway. By constructing a co-expression network of a viper venom gland, we identified the numerous processes working together to produce venom. We identified genes involved in protein folding and degradation to be strongly co-expressed with venom genes. This ‘metavenom’ was key to the evolution of snake venom. It provided tenacity to the venom system to withstand high protein loads and enable the recruitment of diverse proteins into the venom cocktail. This study provides many fundamental contributions to our understanding of the kind of changes, or rather conserved changes needed to enable trait diversification.

Gene duplication can allow a trait to experiment within phenotypic space

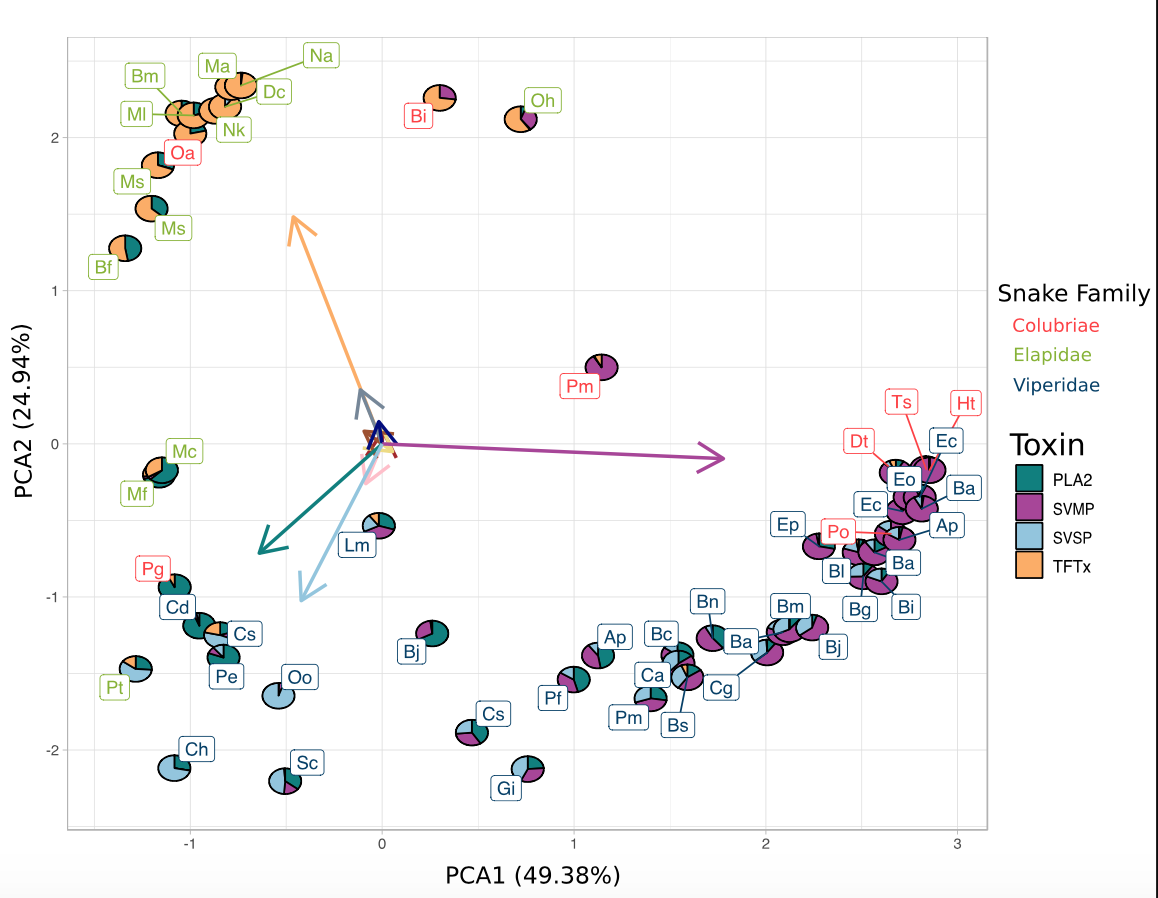

Many genes perform many different functions. This pleiotropic nature of genes can limit the evolvability of a trait. One way to perhaps escape the shackles of pleiotropy is to have duplications, where one gene duplicate can perform its original function. At the same time, the other can evolve freely (as long as it doesn’t become deleterious). This mechanism is one of the ways gene duplication is believed to contribute to trait diversification. However, examples of this are rare. In our ‘Many Options’ study, we show that this mode of evolution is likely the way snake venom evolves. Being composed of many duplicated genes increases toxin dosage in the venom. Furthermore, the freely evolving nature of the gene duplicates helps diversify the phenotype by enabling experimentation with different combinations and amounts of toxins. This mechanism has allowed snakes to occupy different optima in phenotypic space, and the movement between optima is likely the way venom evolves through long timescales.

Many genes perform many different functions. This pleiotropic nature of genes can limit the evolvability of a trait. One way to perhaps escape the shackles of pleiotropy is to have duplications, where one gene duplicate can perform its original function. At the same time, the other can evolve freely (as long as it doesn’t become deleterious). This mechanism is one of the ways gene duplication is believed to contribute to trait diversification. However, examples of this are rare. In our ‘Many Options’ study, we show that this mode of evolution is likely the way snake venom evolves. Being composed of many duplicated genes increases toxin dosage in the venom. Furthermore, the freely evolving nature of the gene duplicates helps diversify the phenotype by enabling experimentation with different combinations and amounts of toxins. This mechanism has allowed snakes to occupy different optima in phenotypic space, and the movement between optima is likely the way venom evolves through long timescales.

Key innovations are not enough to drive species diversification

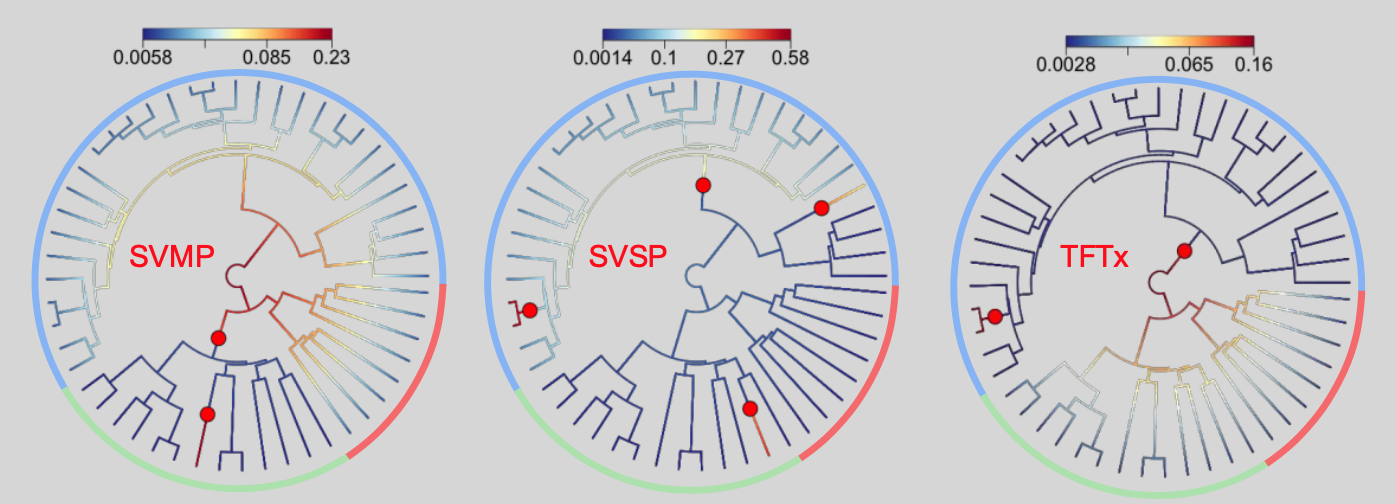

What drives species evolution is a topic of hot debate. There is no one answer, and therefore not one feature, of the animal or the environment that drives speciation. So imagine my surprise when I realised that snake venom is often attributed as the cause for the diversification of venomous snakes. Snake venom is a key innovation, but its role in speciation was never tested, not even remotely. Although difficult to do and requiring a large amount of data, we nonetheless performed a few analysis in our ‘Toxin rates’ paper. We describe how venom in snakes evolves by transitions in evolutionary rates (like how key innovations behave), but they don’t coincide with points of species diversification (which traits involved in speciation are expected to). Furthermore, early burst models, which are supposed to be a feature of traits driving diversification, are poorly supported.

What drives species evolution is a topic of hot debate. There is no one answer, and therefore not one feature, of the animal or the environment that drives speciation. So imagine my surprise when I realised that snake venom is often attributed as the cause for the diversification of venomous snakes. Snake venom is a key innovation, but its role in speciation was never tested, not even remotely. Although difficult to do and requiring a large amount of data, we nonetheless performed a few analysis in our ‘Toxin rates’ paper. We describe how venom in snakes evolves by transitions in evolutionary rates (like how key innovations behave), but they don’t coincide with points of species diversification (which traits involved in speciation are expected to). Furthermore, early burst models, which are supposed to be a feature of traits driving diversification, are poorly supported.

More data and a more elegant analytical approach is necessary to understand either the direct or indirect role venom plays is species evolution. But I thoroughly enjoyed writing this paper and studying the literature.